There was a silver lining that came from the government-mandated, stay-at-home order for Michael and Jen Schron: More time spent with their foster children.

Siblings Nicholas and Noah, 10, and 5-year-old Natalia were separated and receiving out-of-home foster care in Port St. Lucie and Vero Beach when Michael and Jen Schron, of Kissimmee, met the children in December.

The couple was always looking to adopt when they decided to get involved in the child-welfare system, Michael Schron said, and it didn’t take long for the sibling group to move into the Schron’s house.

Everyone was getting acclimated to a new life at home when the coronavirus pandemic hit, but little did the Schron family know it would be a catalyst in the adoption process.

“I think that COVID-19 was the trigger for our kids being able to truly bond with us and then never wanting to leave,” Michael Schron said.

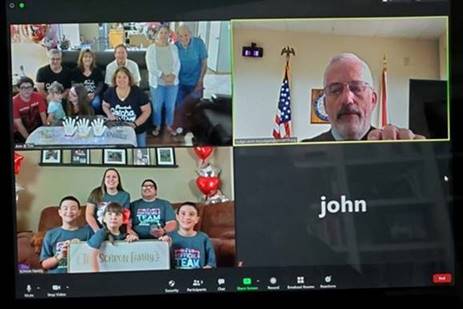

Michael and Jen Schron legally adopted Nicholas, Noah and Natalia on June 9, much faster than the couple had anticipated.

“A family is what the kids advocated they always wanted, and a family is what they got,” Michael Schron said. “The bond that we have with these children, you’d never know they weren’t biologically our kids.”

The Schron children are just three of the 189 adoptions in Martin, St. Lucie, Indian River and Okeechobee counties to be finalized last fiscal year — a 14% increase compared to previous data and 44% higher than the Department of Children and Family’s goal for the area.

“It’s overwhelming and great, because the children need it,” said Vernee Mason, of Children’s Home Society, the agency responsible for overseeing adoptions. “They need the love. They need the stability.”

The fiscal year ran from July 1, 2019 to June 30, coming to an end in the midst of a global pandemic that complicated an already stressful and lengthy process.

Children’s Home Society had to wait for clearance from DCF to perform virtual home studies, train potential adoptive parents in online classes and legally finalize adoptions through Zoom calls due to court room closures, Mason said.

It definitely stalled the process, she added, and there were no adoptions finalized the entire month of March. Once operations were back on track, to Mason’s surprise adoptions didn’t slow down again.

There was also a surge in residents reaching out to the organization to foster and adopt children. Staff started noticing the influx in inquiry calls in late March and early April — at the very start of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ stay-at-home order.

“Their life has slowed down, and they’re able to notice (the problem) and step up,” Mason said. “I’ve seen more families reach out wanting to adopt more than I have in a long time.”

There was a slight decrease in the number of families in the child-welfare system going into the new fiscal year compared to last year, said Christina Kaiser, of Communities Connected for Kids, a local nonprofit responsible for the oversight and coordination of the child-welfare system.

As of July 1, there were:

- 344 children receiving “in-home care”

- 669 children removed from their home

- 352 living with relatives

- 281 in a licensed foster home

Over the last few years in general, though, more children have been entering the system due to the opioid crisis. The substance abuse significantly alters a parent’s behavior, Kaiser said, and often leads to termination of parental rights — causing children to receive out-of-home care for longer time periods and eventually be available to adopt.

“We tend to see that when there’s a rise in drug use there’s also a rise in adoptions,” Mason said.

Child abuse and neglect reports have been down since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, adoption officials said, but that’s not necessarily a good thing.

A majority of these reports come from educators who see children daily, Kaiser said. When COVID-19 shuttered classrooms in March and a stay-at-home order quickly followed, less people were seeing children. The organization is worried about reporting that couldn’t be done.

The three main drivers of child abuse and neglect — domestic violence, substance abuse and mental illness — may have been heightened amid the pandemic, quarantine and economic downturn, she said.

“All those things together, yeah we were a little concerned,” Kaiser said. “We’re definitely expecting to see an impact in the coming months. Not sure to what extent, but I think we would all be doing a disservice to child welfare if we weren’t planning for increases (in reports).”

Typically, there is always an uptick in reports when kids go back to school in the fall, she said.

Educators are not only going to have to keep a close eye on those physically in the classroom, but also the students who opted for virtual learning, she said.

Originally posted by: TCPalm